In our previous blog about mission protection for traditional companies, we discussed how golden shares, a type of share with special voting- or other rights, could be used as a tool to preserve an entity’s social mission. In this blog, we discuss voting trusts and voting agreements as another mission-anchoring mechanism for a tradition entity form.

Voting Trusts

“Adroit lawyers have invented the ingenious device of a voting trust to give what is in essence a joint irrevocable proxy for a term of years the ‘protective coloring’ of a trust, so that the trustees may vote as owners rather than as mere agents.”[i]

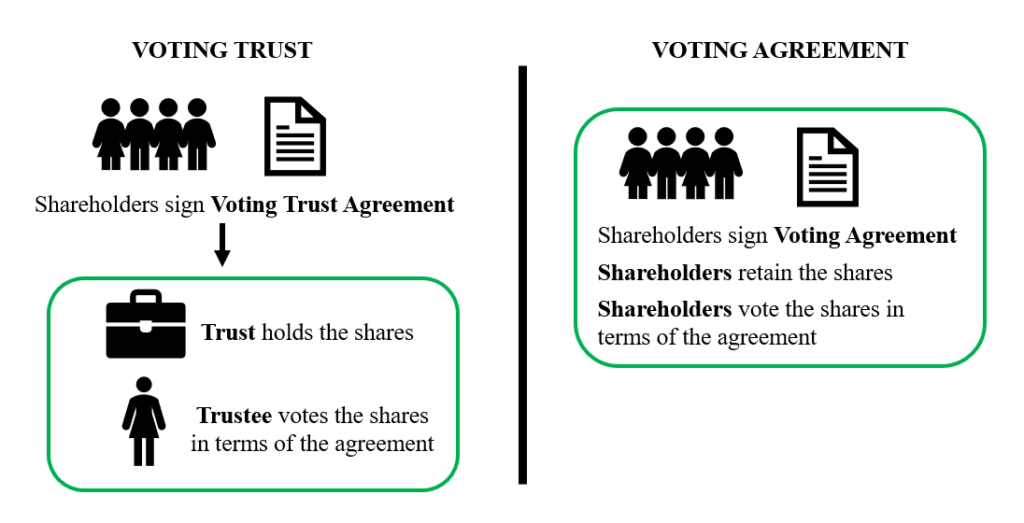

A voting trust is a trust of stock created by way of a voting trust agreement in terms of which shareholders transfer their shares to a trust and delegate their voting authority to the trustee of the voting trust. The trustee is the record holder of the shares and legal title is held by the trust itself; the trustee is given the authority to vote the shares as directed by the trust agreement and distribute the proceeds from the trust. The shareholders retain a beneficial interest in the company’s stock and receive all dividends and distributions of profits payable to the equity shareholders. A voting trust is similar in function to a golden share scheme in that the trustee is given direction regarding how to vote the shares of the trust. Voting trusts are typically irrevocable for a period of years, for the life of a specific person, or until the company dissolves or is sold. The duration of the trusts varies from state to state, and some impose a limitation of up to 10 years for voting trustees.

Voting trusts were created more than a century ago to side-step revocability of proxies and invalidity of pooling agreements.[ii] At that time, American courts disapproved of this mechanism mainly because it regarded the separation of voting rights from stock ownership as contrary to public policy.[iii] In a seminal 1904 case, Warren v. Pim,[iv] the court held that a voting trust was “a masterpiece of professional ingenuity which confides absolute and uncontrolled discretion to a group whose personal stake in the success of the company is so insignificant it may be disregarded entirely.”[v] The judge also remarked that the voting trustee is “only a sham owner vested with a colorable and fictitious title for the sole purpose of permanently voting upon stock that [s/he] does not own.”[vi] However, courts started analyzing the purposes of the trusts and discovered that these trusts were not intrinsically reproachful and thus not invalid per se. In 1958, George B. Davis made the following generalization: “Those [voting trust] agreements which tend to promote the continued welfare of the corporation will stand while those advancing the selfish interests of the few will be struck down.”[vii] (Our emphasis)

Currently, most states have corporate laws authorizing and regulating the use and terms of voting trusts. The legality and validity of a specific voting trust will depend on compliance with statutory requirements and the purposes of the trust agreement. A ‘proper’ purpose will depend on the circumstances of each case. We believe that mission protection is innately a legitimate, proper, and bona fide purpose.

Voting Agreements

Instead of delegating voting authority to a third party (like in a voting trust), shareholders can agree to vote in a specific manner by way of a voting agreement. It is common for start-ups that have raised some venture capital to use voting agreements to allow the investors to appoint a director to the board that cannot be removed. A voting agreement could be drafted to ensure that shares are voted to protect the mission of the entity.

Voting agreements may be faster and easier than voting trusts, as legal title of the shares is not transferred and the entity need not receive a copy of the agreement; it may also be less expensive than voting trusts, as there are no trustee-fees to pay. Voting agreements may be perpetual, which might put off shareholders who do not want to be bound for an unlimited period of time; however, a perpetual agreement could be beneficial for long-term protection of the mission of the entity. Like any contract, voting agreements may be enforced between the parties themselves, by alternative dispute resolution, or in court.

Visual Comparison

If you wish to use either of these mechanisms, be sure to consult an attorney to ensure that the voting trust or voting agreement is specifically permitted and enforceable under applicable law.

In our next blog post, we will discuss a dual share class as a device to anchor a company’s mission.

[i] Ballantine, Voting Trusts, Their Abuses and Regulation (1942) 21 TEX. L. REv. 13Q.

[ii] Voting Trusts in Texas, 12 Sw L.J. 85 (1958)

[iii] Woloszyn, John J. (1975) “A Practical Guide to Voting Trusts,” University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol4/iss2/4.

[iv] 66 N. J. Eq. 353 (1904).

[v] Id. at 364, 59 A. at 781.

[vi] Id. at 386, 59 A. at 785.

[vii] Voting Trusts in Texas, 12 Sw L.J. 85 (1958).